Peggy Malone walks the quiet halls of Crozer-Chester Medical Center, the Pennsylvania hospital where she’s worked as a registered nurse for the past 35 years, with the feeling she’s drifting through a ghost town.

The sprawling hospital serves the diverse and densely packed Philadelphia suburb of Upland, and a large proportion of its patients earn low incomes. Malone remembers a time when the hospital, once the largest in the county with nearly 500 licensed beds, was such a hub that neighbors would come to the cafeteria just to have dinner.

Now many of the units sit empty. Gone are the pediatric unit, the transplant program, the surgical residency and the detox program where Malone used to work. Staff has been reduced and supplies are scarce.

Patients’ rooms in the main building haven’t had television since the cable was disconnected last month, she said.

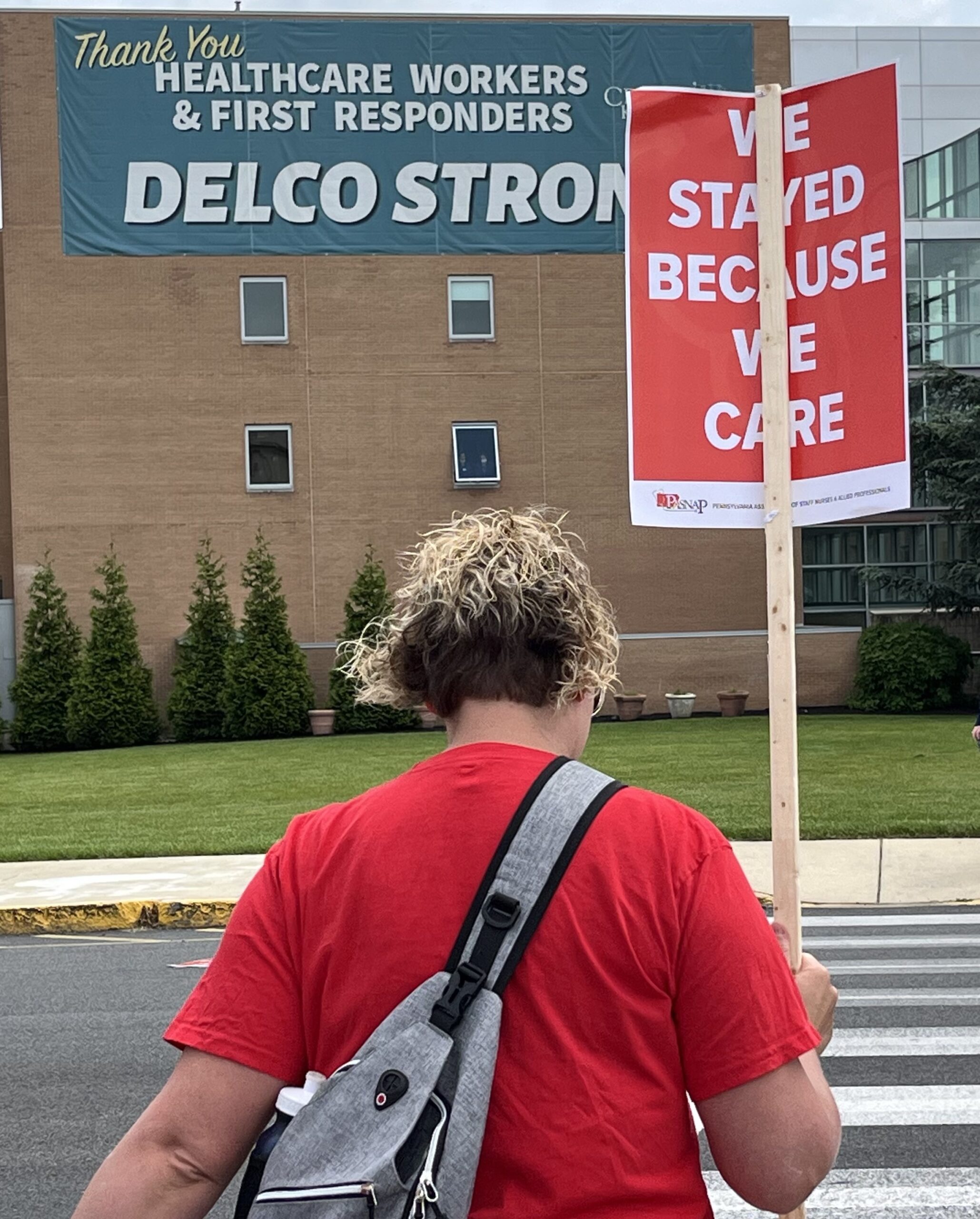

Malone has grown accustomed to telling this story over and over to reporters, to researchers, even to Congress in recent years. Her community — her hospital — is a cautionary tale for what can happen when private equity comes to town.

“We want to give good patient care,” she told Stateline. “We want to not be using broken equipment and piecing supplies together. But we don’t have the power to stop what’s happening.”

Private equity firms use pooled investments from pension funds, endowments, sovereign wealth funds and wealthy individuals to buy controlling stakes in companies. In the past couple of years, private equity’s foray into hospital ownership has drawn public outrage and, increasingly, legislative scrutiny.

“It’s now a familiar story,” U.S. Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, a Rhode Island Democrat, said last month in a statement announcing a bipartisan investigation with Iowa Republican Sen. Chuck Grassley into the impacts of private equity ownership of hospitals. “[P]rivate equity buys out a hospital, saddles it with debt, and then reduces operating costs by cutting services and staff — all while investors pocket millions. Before the dust settles, the private equity firm sells and leaves town, leaving communities to pick up the pieces.”

That “familiar story” played out in Malone’s backyard.